|

"I've learned that no matter what happens, or how bad it seems today, life does go on, and it will be better tomorrow. I've learned that you can tell a lot about a person by the way he/she handles these three things:

a rainy day, lost luggage, and tangled Christmas tree lights. I've learned that

regardless of your relationship with your parents, you'll miss them when they're

gone from your life. I've learned that making a living is not the same thing as

making a life. I've learned that life sometimes gives you a second chance.

I've learned that you shouldn't go through life with a catcher's mitt on both

hands; you need to be able to throw some things back. I've learned that whenever

I decide something with an open heart, I usually make the right decision. I've

learned that even when I have pains, I don't have to be one. I've learned that

every day you should reach out and touch someone. People love a warm hug, or

just a friendly pat on the back. I've learned that I still have a lot to learn.

I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you

did, but people will never forget how you made them feel."

|

| ~Maya Angelou |

|

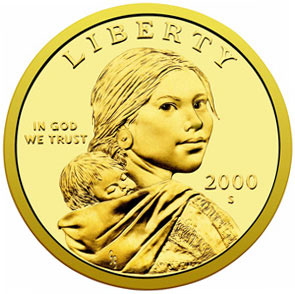

In 1800, when she was about 12 years old, Sacagawea was kidnapped by a war party of Hidatsa Indians -- enemies of her people, the Shoshones. She was taken from her Rocky Mountain homeland, located in today's Idaho, to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages near modern Bismarck, North Dakota. There, she was later sold as a slave to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader who claimed Sacagawea and another Shoshone woman as his "wives." In November 1804, the Corps of Discovery arrived at the Hidatsa-Mandan villages and soon built a fort nearby. In the American Fort Mandan on February 11, 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to her son Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, who would soon become America's youngest explorer. Sacagawea, with the infant Jean Baptiste, was the only woman to accompany the 33 members of the permanent party to the Pacific Ocean and back. Baptiste, who Captain Clark affectionately named "Pomp" or "Pompy" for his "little dancing boy" frolicking, rode with Sacagawea in the boats and on her back when they traveled on horseback. Her activities as a member of the Corps included digging for roots, collecting edible plants and picking berries; all of these were used as food and sometimes, as medicine. On May 14, 1805, the boat Sacagawea was riding in was hit by a high wind and nearly capsized. She recovered many important papers and supplies that would otherwise have been lost, and her calmness under duress earned the compliments of the captains. On August 12, 1805, Captain Lewis and three men scouted 75 miles ahead of the expedition's main party, crossing the Continental Divide at today's Lemhi Pass. The next day, they found a group of Shoshones. Not only did they prove to be Sacagawea's band, but their leader, Chief Cameahwait, turned out to be none other than her brother. On August 17, after five years of separation, Sacagawea and Cameahwait had an emotional reunion. Then, through their interpreting chain of the captains, Labiche, Charbonneau, and Sacagawea, the expedition was able to purchase the horses it needed. Sacagawea turned out to be incredibly valuable to the Corps as it traveled westward, through the territories of many new tribes. Some of these Indians, prepared to defend their lands, had never seen white men before. As Clark noted on October 19, 1805, the Indians were inclined to believe that the whites were friendly when they saw Sacagawea. A war party never traveled with a woman -- especially a woman with a baby. During council meetings between Indian chiefs and the Corps where Shoshone was spoke, Sacagawea was used and valued as an interpreter. On November 24, 1805, when the expedition reached the place where the Columbia River emptied into the Pacific Ocean, the captains held a vote among all the members to decide where to settle for the winter. Sacagawea's vote, as well as the vote of the Clark's manservant York, were counted equally with those of the captains and the men. As a result of the election, the Corps stayed at a site near present-day Astoria, Oregon, in Fort Clatsop, which they constructed and inhabited during the winter of 1805-1806. While at Fort Clatsop, local Indians told the expedition of a whale that had been stranded on a beach some miles to the south. Clark assembled a group of men to find the whale and possibly obtain some whale oil and blubber, which could be used to feed the Corps. Sacagawea had yet to see the ocean, and after willfully asking Clark, she was allowed to accompany the group to the sea. As Captain Lewis wrote on January 6, 1806, "[T]he Indian woman was very impo[r]tunate to be permited to go, and was therefore indulged; she observed that she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters, and that now that monstrous fish was also to be seen, she thought it very hard she could not be permitted to see either." On January 6, 1806, Sacagawea gazed in awe across an immense body of water. Towering waves crashed on the beach before her. She was extremely tired but gratified. She had helped the expedition reach its final destination- the Pacific Ocean. During the expedition's return journey, as they passed through her homeland, Sacagawea proved a valuable guide. She remembered Shoshone trails from her childhood, and Clark praised her as his "pilot." The most important trail she recalled, which Clark described as "a large road passing through a gap in the mountain," led to the Yellowstone River. (Today, it is known as Bozeman Pass, Montana.) The Corps returned to the Hidatsa-Mandan villages on August 14, 1806, marking the end of the trip for Sacagawea, Charbonneau and their boy, Jean Baptiste. When the trip was over, Sacagawea received nothing, but Charbonneau was given $500.33 and 320 acres of land. Six years after the expedition, Sacagawea gave birth to a daughter, Lisette. On December 22, 1812, the Shoshone woman died at age 25 due to what later medical researchers believed was a serious illness she had suffered most of her adult life. Her condition may have been aggravated by Lisette's birth. At the time of her death, Sacagawea was with her husband at Fort Manuel, a Missouri Fur Company trading post in present-day South Dakota. Eight months after her death, Clark legally adopted Sacagawea's two children, Jean Baptiste and Lisette. Baptiste was educated by Clark in St. Louis, and then, at age 18, was sent to Europe with a German prince. It is not known whether Lisette survived past infancy. more on the life of sacagawea and pomp reference: above text from PBS Lewis & Clark |

Hereby bestowed,

title of Honorary Dancing Bears

to Sacagawea and her son, Pomp!

Talk about Inspiration!

Why Not?

Visit Merry Prankster

Cathy Casamo

(aka Stark Naked)'s

Cool New Homepage

home to

merovence

surf mac